Home Defence and the Farmer

If this country were to be attacked with nuclear weapons, many farms would be damaged or set on fire, even though they might be well away from where the explosions occurred. In addition, there would be a grave risk that highly dangerous radioactive dust (or fall-out) resulting from the explosions would be spread over wide areas of the countryside.

The continuance of food production on farms affected by fallout could well depend upon the practical steps taken by each farmer and his staff at a time when they would be on their own, with no one to turn to for advice or help. The handbook can only suggest in general terms how livestock and crops could be safeguarded. If an attack came, farmers in all parts of the United Kingdom would suddenly be faced with new and major problems. On their solution, our survival might well depend.

Although mainly concerned with farming

matters, the handbook also deals briefly with the danger

to the farmer and his family from radioactive fall-out

and how they might protect themselves. There is much more

information on these non-farming aspects of civil defence

in the Home Office publications The Hydrogen Bomb and

Nuclear Weapons.

The Hydrogen Bomb, H.M.

Stationery Office, 1957. (9d.)

Nuclear Weapons, H.M. Stationery Office, 1956 (2s. 6d.) |

These handbooks do not

deal with all the difficulties that would face farmers if

this country were to be attacked with hydrogen bombs. In

addition to the fires, destruction and fall-out, there

would certainly be serious shortages of farming

requisites and difficulties in moving farm produce.

The handbook also does not deal, except in passing, with the Government's plans for dealing with the consequences of radioactive fall-out on farms; for example, measures to deal with the large numbers of livestock that may sicken or die as a result of radiation; plans to control the movement of farm produce which may be dangerous through contamination by radioactive material. These, and other defence plans affecting farming, are being worked out on the basis of facts such as are presented in the following pages.

It is important that a clear distinction should be made between fall-out which would arise if this country were attacked with nuclear weapons and fall-out resulting from the peace time testing of such weapons. Deposits of radioactive fall-out in peace time, although measurable, are both infinitesimal and negligible in comparison with what might be expected in war time, and it is accordingly emphasised that this handbook deals only with problems associated with the war time hazard. The same problems do not arise in peace time.

Dangers from atomic or hydrogen

bombs

When an atomic or hydrogen bomb bursts, there is a

very great destruction from fire and blast for several

miles around. But there is also another kind of danger

which can affect a very much larger area. This danger

comes from radioactive fall-out from the bomb.

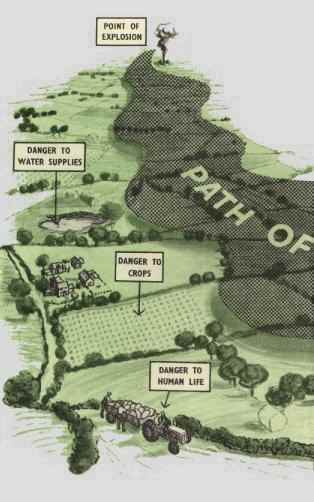

Radioactive fall-out

If a hydrogen bomb or atom bomb explodes on or near

the surface of the earth, masses of soil and debris are

drawn upwards to form a great cloud very high in the air.

This cloud contains radioactive particles produced by the

explosion; that is to say, particles which give off

radiations rather like X-rays. These radiations can harm

human beings and animals. Some of the particles are very

fine, like dust, and others are much bigger. The bigger

particles quickly fall to earth again near to where the

bomb exploded, but high in the air the fine particles are

blown along by the wind, just as chalk dust is blown

about when a farm is being limed. These fine particles

slowly come down to earth, all the time giving out their

harmful radiations. Fall-out is the name given to

this fine dust.

In the case of an attack with hydrogen bombs, the fall-out might spread over a very large area, stretching for hundreds of miles downwind from where the bomb bunt. Usually you would not be able to see this fine radioactive dust, even though it was falling on to your house, your buildings, your fields and your animals. Neither could you hear, feel or smell fall-out. Nevertheless, the dangerous radiations would still be there and they could be detected on special instruments. But if you did see a dust cloud after a bomb had gone off, you should take shelter at once.

Fall-out is dangerous

Fall-out is dangerous because every particle of it

gives out rays like X-rays which can damage or destroy

the living cells of the human body. It is more harmful

the nearer you are to it) or if it gets on your skin or

clothing. The rays can penetrate the walls of a building

to some extent, but even so you are much safer inside a

building than outside.

It is also dangerous to swallow fall-out in food or water. This is because once fall-out gets into your body, some of it will stay there; all the time it is there its rays are attacking the sensitive internal organs of the body and illness or death may result.

Danger to animals

Animals are harmed by fall-out just as are human

beings. Indeed, they would probably be affected more

severely because, unless they were in buildings, they

would be exposed to the full effect of the radiation day

and night. Most human beings would be able to protect

themselves by taking shelter.

Danger to milk supplies

If livestock were grazing pasture on which there had

been fallout, not only would they be exposed to the

radiation from the fall-out on the ground around them but

also internally from the fall-out on the grass they had

eaten. Some of this fall-out would pass through their

bodies, but some would be retained and continue to cause

damage. In the case of dairy cows, some of the fall-out

would pass through the cow to the milk. It would be

dangerous for human beings to drink such milk, even

though the amount of radioactive material in it might

only be small. In fact, even in districts where the fall-out

was not sufficiently severe for it to cause any direct

harm to human beings, cows might pick up sufficient fall-out

on their grazing to make their milk dangerous for humans,

and particularly infants, to drink.

Other effects of fall-out on farming

If H-bombs were exploded over this country, people in

the very heavy fall-out areas would have to leave after

being in refuge for forty-eight hours, and they would not

be able to return for a considerable time.

People in the less badly affected areas would still have to stay in refuge for forty-eight hours and, after that, would not be allowed out for more than an hour or two a day for the next few weeks.

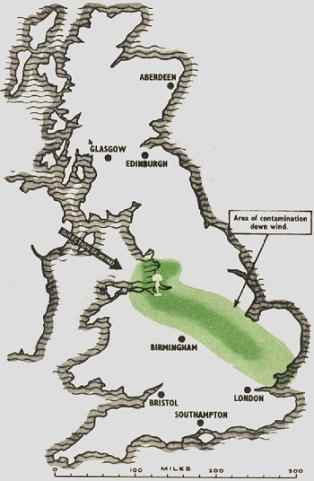

TYPICAL FALL-OUT PATTERN

This diagram illustrates the fall-out pattern from an H-bomb supposedly dropped on the north-west coast, with the wind blowing from a generally westerly direction.

In the lightly contaminated areas, people would be allowed greater freedom after the first forty-eight hours but should not spend more time in the open than was thought by their wardens to be safe.

In some districts losses of livestock would be serious; sowing of crops might be delayed and some time might have to elapse before harvesting could take place. The growth of crops would not be greatly affected in most of the fall-out areas, though the fall-out on them might make them unfit for consumption by humans or animals. It might be necessary to suspend marketing crops for the time being until they had been tested for radioactivity and found to be safe. The Agricultural Departments are training some of their staffs to be able to carry out this testing.

Fall-out warning

Unless it were a misty or rainy day, many people

miles away would see the great ball of fire which would

rise into the air after a hydrogen bomb had exploded, and

with it the vast mushroom-shaped cloud of dust and debris

that would contain the fall-out. The direction which the

fall-out cloud would take would depend on several factors,

including the direction and strength of the winds at

ground level and up to heights of 80,000 feet or more,

where the wind directions might be very different from

those near to the ground.

People who saw the mushroom-shaped cloud would do well to make ready to shelter in case fall-out followed in their area. Plans are being made to give the public warning of the approach of fall-out.

What protection is there against

fall-out?

There are three simple facts about fall-out:

1. The rays from fall-out become less dangerous as time goes on, and, in particular, they lose most of their power within two days of the explosion of the bomb. For example,

100 units of radiation 1 hour after a bomb goes off would be reduced to about

10 units 7 hours later, and still further reduced to

1 unit after 2 days.

Even so, if the fall-out had been particularly heavy, it might still be dangerous to be out of doors after forty-eight hours.

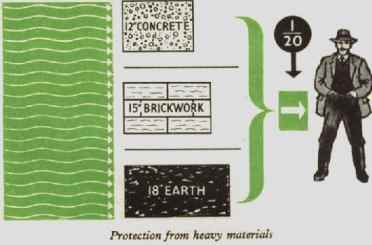

2. The rays are less intense the further you are away from fall-out. If you could keep a distance of 12 feet or so away from the nearest fall-out, you would receive only about two-thirds of the radiation you would otherwise get.

3. The rays are markedly absorbed by heavy materials like brick, concrete and earth. A person shielded by a foot of concrete or 15 inches of brick or 18 inches of earth would receive only one-twentieth of the dose he would get if unprotected.

What do these facts mean in working out how to protect yourself against fall-out?

First of all, if you were in a fall-out district, you would have to stay indoors until told by a civil defence warden, or the radio, that it was safe to come out. Shelter in the cellar if you have one or, failing that, in a protected room on the ground floor of your house.

Secondly, if you and your family were in a shelter with walls giving the equivalent protection of concrete a foot thick and which was such that the fall-out on the ground outside and on the roof was nowhere nearer to you than about 12 feet, the radiation received in the shelter would be only one-thirtieth of that outside in the open. Moreover, by staying inside for the first two days, you would have been having this thirtyfold protection during the time the fall-out was most dangerous. The radiation after two days would be only one-hundredth as dangerous as it had been just after the explosion.

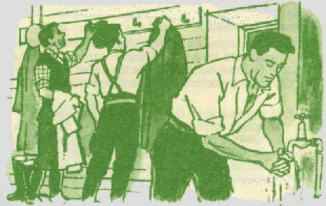

There are two other rules to observe about protection. The first is to keep fall-out off your skin and clothes. When it is on or near your body, it can cause serious burns. So if you believed you had fall-out on your clothes or body, you should change into other clothes at once and wash very thoroughly. The other, and most important, rule is to avoid getting fall-out inside your body, whether through a cut or on food or in water. Once it is inside your body, the radiations can do very great damage to the internal organs and bones.

These rules, and the advice about sheltering in the most substantial building available, can be used to work out measures for protecting your livestock as well as your family.

Even when you were told it was safe to come out of shelter, it might still not be safe to stay out of doors very long. Your warden would tell you whether you could get on with your work without further risk from radiation or whether your farm was in an area where the fall-out had been very heavy and where it would be necessary either for you to leave your farm for a time or, for your own safety, not to spend more than a few hours a day in the open for the time being.

Although fall-out would be very dangerous, there are some useful precautions you could take to protect your family and your farm. Not all farms would be affected, but it is worth while taking these precautions because if hydrogen bombs were to explode in this country a very large number of farms would be affected to a greater or less extent and yours might be one of them. Moreover, many of the measures that would reduce the risk from fall-out are also good farming practice in peace time and worth adopting purely for their peace time value.

For example, in peace time, well-managed pasture or fodder crops lead to lower production costs; in war time, livestock would come to less harm from fall-out in grazing a thick quick-growing pasture or fodder crop than if they were on a poor pasture where they had to graze a large area to get their food. The farmer with ample silage and hay would be able to feed it to his dairy cattle and avoid or delay putting them out on to contaminated pasture.

Even the layout of buildings, yards and roads would help, not only in peace time but in fall-out conditions in war time. A good layout would help the farmer and his men to reduce the time spent out of doors and so minimise the dose of radiation they might receive. So efficient farming is not only in the national interest and the farmer's interest in peace time, but it is a way of preparing for safer farming if another war should occur.

If you had a few months' warning of

the possibility of war

Supposing there were to be a few months' warning of a

war, these are some of the things you could do to make

your family safe if fall-out should come:

Get ready to act on the advice in this handbook, and make sure you arrange things so that you can make the best use of a few hours' warning of fall-out.

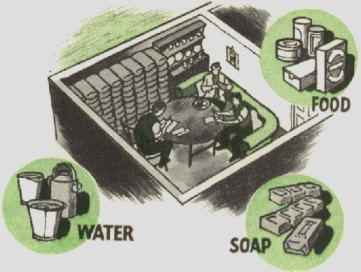

Make your cellar habitable and as comfortable as you can. If you haven't a cellar, prepare a refuge room in the house. Keep a stock of tinned and packaged food in your house and some containers to hold drinking water for your family. A supply for two or three weeks would be a wise precaution. A stock of soap would also be useful for personal decontamination if you were to get fall-out on your skin.

These things would help to make your farm safer if fall-out should come:

Work out in advance whether you have shelter for dairy cattle and other livestock; try housing them one day to see how long it would take.

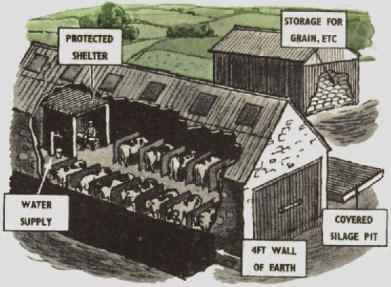

Remember that the fall-out might be so dangerous that you would have to stay indoors for two days after it came down. This means that you might not be able to get out to milk your cows and they might be in considerable pain by the time you could milk them again. Probably the best thing you could do would be to provide yourself, or one of your men, with a protected shelter (for example, a loose box protected by a thick layer of earth) in the cowshed and equip it with a bed. Whoever stayed in it could leave it for long enough to ease the cows if they were in pain, but milking should be left as late as possible in the two-day period to allow the intensity of radiation to die down before leaving the comparative safety of the shelter to work in the less well protected cowshed. If necessary the milk would have to be wasted.

Arrange your farming so that essential things are near the house or near the livestock buildings. For example, a mains tap outside the buildings (or better still, inside them), might be very useful. Have your silage pits as near as possible to the buildings where your livestock would be sheltering from fall-out; the shorter your journey in the open, the less exposed to fall-out you would be. But in siting your haystacks, remember the risk of their being fired either by a bomb or through natural causes. Have a store of fodder always inside your buildings, and if the roofs are poor, have some tarpaulins ready to put over them.

A wall of earth 3 or 4 feet high against the livestock buildings would add to the protection against radiation which the walls would give your livestock. For example, a potato clamp built against walls of a building would be useful protection.

Store as much clean water as you can for your animals which are under cover. It must be near the buildings. If you have a well, see that it is kept clean and covered. Put some tubs and other containers beside your buildings and keep them covered. Fill them regularly with clean water.

Get hurdles or fencing ready so that cattle could, if necessary after the attack, be confined to a small area of grazing.

Make sure any seed or grain is in a weatherproof building into which fall-out would not penetrate, and that your windows, doors and roofs are in good repair or covered over.

If you are short of shelter for your livestock and have a Dutch barn, build up bales of straw at the sides and ends. The straw would not stop the radiation from fall-out to any extent, but the makeshift walls would reduce the risk of fall-out dust getting on the coats of animals sheltering under the barn and would keep the fall-out at a distance from them.

Try to have some satisfactory storage space for fuel (a fuel tank is a good investment in peace time), fertilisers, feeding-stuffs and seeds. If there were to be a few months' warning of a war it might be possible to arrange with the trades concerned to move supplies of these requisites on to farms.

If a war threatened, the Government would supply you with more detailed advice about the farming problems you might have to face and what it would want you to grow. There might be time for you to adjust your farming programme accordingly.

Warning, after an outbreak of war,

of the approach of fall-out

First of all, make arrangements for the safety of

your family, your workers and yourself. Don't forget to

take enough farm and garden produce into the house to

last you for a week or two. Keep a spare set of clothes

handy which you would use only outside the house;

by changing them when you came in, you would avoid taking

fall-out into the house. If you have made a protected

shelter in the cowshed, make sure that there is some food

and water in it.

THESE

ARE THE THINGS YOU MIGHT

SEE TO ON THE FARM

Livestock

The nation would need all the clean milk it could get.

Therefore get everyone busy first bringing in the dairy

cattle and the calves if possible into a building by

themselves. Then, if you can, get your other livestock

into buildings or a yard or, failing that, to a small

field. If any animals had to be left in the open choose a

sheltered field. Trees would give some protection.

Do what you can to reduce the milk yield of your cows temporarily to ease their pain, in case you cannot get out to milk them for a day or two.

Thus:

Milk them out before leaving them.

Leave just sufficient food to keep them alive; it would be best to give them poor quality fodder, such as straw. The supply of water to drinking bowls should be cut down.

Wherever possible, house any calves you have with the milking cows so the cows can suckle them.

Other animals can have food and water if you have time to get any in, but give them as little as is necessary to keep them alive. You may need all the clean food you have for feeding dairy cattle if the fall-out comes.

Fodder

Bring under cover as much food as possible for your

live-stock, or put a tarpaulin over it (for example, if

you have an open silage pit or any grain in stack).

Water

You cannot rely in advance on a continuing mains

supply-therefore store as much water as possible. Well

water is likely to be safe if you have put a cover over

the well to prevent contamination by fall-out. But if the

well had not been in use for some time, you should boil

the water or add hypochlorite at the rate of ½

teaspoonful to 10 gallons of water before using it for

human consumption. If you have a rain-water butt make

sure that you can turn the spout away so as to stop the

rain washing fall-out from the roof into your clean water.

Cover the butt itself. If you have a stream running

through your farm you need not worry so much about water

for your livestock, as the stream is likely to be safe

for livestock to drink, especially if it is fast flowing.

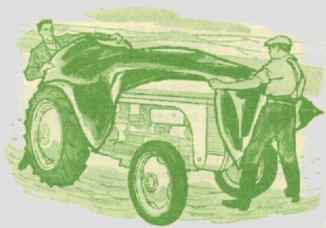

Implements and Machinery

If you still have time, bring your vehicles and

tractors near to the farm-house and under cover if

possible; alternatively, cover them with tarpaulins or

sacks. But only bother with machinery and implements

after you have seen to your livestock. Food and water

come first.

If there were to be an attack on this country with nuclear weapons, and you had had to shelter from fall-out, you would want to know, when you were told it was safe to leave shelter:

whether the food on your farm would be safe to eat;

what you could do to reduce the risk from fall-out; and

what you ought to be doing on your farm.

FOOD FOR YOUR FAMILY

The food in your larder would be safe to eat, provided it was in sealed containers or otherwise protected so that no dust from outside could get on to the food.

There would also probably be food on the farm which you would want to use if you knew it was safe to eat or knew how to make it safe.

The following paragraphs give some advice on dealing with food produced on your farm.

MILK

There would be a very great

risk in drinking milk from cows which have eaten food

contaminated by fallout. If your family badly needed milk,

it should be given to them only if you were sure that

your cows had been under shelter before the fall-out came

down and had not left it since, and that they had had

only food and water on which there could have been no

fall-out dust.

MILK

There would be a very great

risk in drinking milk from cows which have eaten food

contaminated by fallout. If your family badly needed milk,

it should be given to them only if you were sure that

your cows had been under shelter before the fall-out came

down and had not left it since, and that they had had

only food and water on which there could have been no

fall-out dust.

EGGS

It would be safe to use eggs

from poultry that had been under cover the whole time

since the fall-out came down. It would not be quite so

safe to use eggs from poultry on open range, but they

could be used if badly needed as food, since the risk

from fall-out would be only slight.

EGGS

It would be safe to use eggs

from poultry that had been under cover the whole time

since the fall-out came down. It would not be quite so

safe to use eggs from poultry on open range, but they

could be used if badly needed as food, since the risk

from fall-out would be only slight.

POTATOES AND ROOTS It would be safe to use fully grown potatoes and

root crops ready for harvesting, provided they were well

washed to remove all soil particles and also peeled. It

is important that the fall-out should be removed; it is

not destroyed by boiling or cooking (see below-'Growing

Plants').

POTATOES AND ROOTS It would be safe to use fully grown potatoes and

root crops ready for harvesting, provided they were well

washed to remove all soil particles and also peeled. It

is important that the fall-out should be removed; it is

not destroyed by boiling or cooking (see below-'Growing

Plants').

GREEN VEGETABLES It is better not to eat green vegetables which

might be contaminated by fall-out. But if in the first

few days after the attack you had to take the risk of

eating green vegetables choose only plants with solid

hearts such as cabbage, sprouts and lettuces. Several

layers of the outer leaves would have to be removed and

the heart washed thoroughly before cooking. The discarded

leaves should not be kept indoors. Loose-hearted cabbages,

etc., would not be fit to use, as there might be fall-out

on the leaves. In dealing with all garden produce, it

would be advisable to wear gloves, preferably rubber, to

keep contamination away from the skin. You should scrub

your hands paying particular attention to your nails.

GREEN VEGETABLES It is better not to eat green vegetables which

might be contaminated by fall-out. But if in the first

few days after the attack you had to take the risk of

eating green vegetables choose only plants with solid

hearts such as cabbage, sprouts and lettuces. Several

layers of the outer leaves would have to be removed and

the heart washed thoroughly before cooking. The discarded

leaves should not be kept indoors. Loose-hearted cabbages,

etc., would not be fit to use, as there might be fall-out

on the leaves. In dealing with all garden produce, it

would be advisable to wear gloves, preferably rubber, to

keep contamination away from the skin. You should scrub

your hands paying particular attention to your nails.

![]() PEAS AND BEANS Only

the pods of peas and beans would be contaminated. The

peas and beans inside would be quite safe to eat.

PEAS AND BEANS Only

the pods of peas and beans would be contaminated. The

peas and beans inside would be quite safe to eat.

But in the case of growing plants there would be the danger after the first few days that potatoes and other root crops, as well as peas and beans and the leaves of cabbages, might be contaminated by radioactive material which had been taken up through the root system from the soil (see Fall-out in the growing season). If the fallout came during the growing season it would be better to have the crops tested for radioactivity before eating them. But if food was so scarce that you had to eat growing plants which might be contaminated, it would be safer to use potatoes, then peas and beans, then green vegetables, in that order.

REDUCING THE RISK FROM FALL-OUT

There is no known way of preventing the fall-out from giving out its radiations, nor of speeding up the rate at which the intensity of the radiations dies away. All you can do is to move the fall-out to a place where it can do least harm.

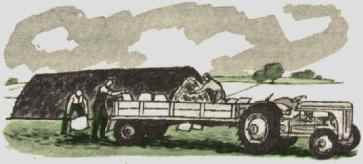

In the few hours each day when it would be safe to be out, your first job would be to see to your livestock. Then if you had plenty of water you could hose down the roofs and buildings, also any made-up surfaces or hard roadways there may be around your buildings. If you had little or no stored fodder, some nitrogen could be put on to a well-grazed pasture. It would speed up the growth of new grazing, which would be very much safer than the older grass that was there when the fall-out came down. Or you could mow some grass, cart it to a place where the animals could not get it and put some nitrogen on the field to encourage new growth.

It would be useful to keep a set of old clothes and rubber boots for outdoor use and to change when you got back home. They should be left in the porch on going indoors. When working, outside gloves should be used, preferably rubber ones, but in any case it would be most important to wash your hands well before eating and to scrub your finger nails well. If you were doing a dusty job - ploughing or cultivating dry land, or threshing or grinding corn or stacking hay - a handkerchief or a simple dust filter should be worn over nose and mouth, and ears should be plugged with cotton wool. Afterwards the nose and ears should be thoroughly cleaned.

Persisting dangers from fall-out

Even several weeks after the fall-out had come down

and when the danger from external radiation might have

died away, it would still be important that farm produce,

especially milk, should be tested for radioactivity,

unless you were advised otherwise by the Agricultural

Departments. This is because fallout consists of a

mixture of many chemicals. All are radioactive. Some of

these chemicals soon lose their radioactivity and so the

intensity of the harmful rays being given off by the fall-out

as a whole diminishes fairly quickly. Even so, if much

fall-out had come down on your land, the rays might

remain dangerous for several months. But if your land was

only slightly contaminated, the danger from external

radiation might last only several hours. This would not

mean that all fall-out had ceased to give off rays. A

small part of it, made up of those chemicals which lose

their radioactivity only slowly, would still be giving

off rays and you should take precautions to keep the fall-out

away from your body.

One of these chemicals, called radioactive strontium, retains its radioactivity for many years. If it got into your body some of it would go into the bones and stay there, all the time giving out radiations which might eventually cause illness or premature death. That is why it is important for food to be tested for contamination before marketing. It is specially important that milk should be tested for radioactivity. This is because even though the amount of radioactive chemicals remaining in a fall-out area might be small enough to permit lifting any restrictions on the length of time people could be outside, dairy cattle on free grazing would collect these chemicals from all the grass they would be eating. In this way they might swallow dangerous amounts of the radioactive strontium, some of which would get into their milk.

If your cows had been under shelter and had had food and water which had had no fall-out dust on it, their milk would almost certainly be safe. Even so, it would be better for it to be tested before it was supplied to the public.

In

war time the country would need all the food it could get

and you should try to avoid wasting any milk produced by

your cows. Milk which was found on test for radioactivity

to be contaminated, or about which you were doubtful and

could not get tested, could be made into cheese or better

still, butter, if you had facilities for doing so. This

would have to be tested for radioactivity later on. If

you had spare churns the milk could be kept for a day or

two until it could be tested. Contaminated milk, whether

whole or separated, could be fed to pigs and steers. This

is because its radioactivity is unlikely to do them very

much harm before they reach the age at which they are

ready for the butcher.

In

war time the country would need all the food it could get

and you should try to avoid wasting any milk produced by

your cows. Milk which was found on test for radioactivity

to be contaminated, or about which you were doubtful and

could not get tested, could be made into cheese or better

still, butter, if you had facilities for doing so. This

would have to be tested for radioactivity later on. If

you had spare churns the milk could be kept for a day or

two until it could be tested. Contaminated milk, whether

whole or separated, could be fed to pigs and steers. This

is because its radioactivity is unlikely to do them very

much harm before they reach the age at which they are

ready for the butcher.

WHAT ELSE TO DO ON YOUR FARM

This handbook is intended to help you through the first few difficult days, or the week or two just after fall-out had come down. It does not deal with the longer-term problems such as how best to get a badly contaminated farm back into production again. This and other problems could best be tackled by advice on the spot in the circumstances of your farm.

Agricultural and other Government Departments are making plans for you to be given advice and help locally on the problems that would face you if ever there should be another war. But in the short term, the advice in this handbook, and that of your warden, would help you in the very difficult conditions that would exist after an attack with nuclear weapons. As long as it was safe to be outside - and your warden would tell you about that - it would be safe for you to carry on farm operations and to harvest your crops. Priority would have to be given to producing uncontaminated milk; remember that a thick, quick-growing pasture would help to reduce the risk from fall-out to the grazing animal.

The remainder of this handbook consists of information on practical questions which farmers are likely to ask about the threat from radioactive fall-out to particular farm enterprises in which they are interested. Though much of the information can be deduced from the facts about fall-out already given, the additional details will probably help farmers to make plans to tackle these entirely new problems, should they ever occur.

If you want further advice, ask your local agricultural officer.

If you are able to get your cows under cover, keep them there as long as possible, and preferably until you are advised that it is safe for them to go out to graze. If a shortage of feedingstuffs forces you to put out your cows earlier, it is better to put them on as small an area as possible, even though it would mean a ternporary loss of milk production, so as to reduce the amount of fall-out getting inside the animals and into their milk.

Should cows be dried off rather than

continue in milk on a contaminated farm?

The advice given above would reduce the yields of

milk. But during the time the dairy cattle were being fed

on stored food (if your silage pit or haystack had not

been protected, it would still be safe to feed your

cattle on them, provided the surfaces exposed to the

atmosphere were removed.), you should cut and cart away

the grass from your pastures, especially if the fall-out

had come in the summer when growth was quick. This

treatment would remove most of the fall-out from the

pastures. Your cows could then graze the new grass as it

grew. The grass taken off could be made into hay or

silage and tested later to see whether it was safe to be

used for fodder. If you had to put your cows outside

without being told it was safe and if you had been unable

to cut the grass, another way to reduce the amount of

fall-out getting into their milk would be to let other

livestock graze the area first.

Even if your cows had to be on contaminated pasture for a time, provided they did not take in sufficient fall-out to cause illness or death, they would still be able to give uncontaminated milk later on. Once they had got back on to an uncontaminated food supply, the amount of radioactive chemicals in their milk would be reduced each day until after a few weeks their milk should be fit for human consumption, though it would need testing first.

Would contaminated milk make milking

machines unfit for use?

No. The ordinary thorough cleansing given to milking

machinery and milk containers would be satisfactory.

Are them special precautions for

handling dairy cattle and other livestock exposed to fall-out?

Yes. If your animals had been exposed to fall-out,

their coats would have trapped the dust, and you should

wash your hands thoroughly after handling them. Where

practicable, the best thing would be to clip their hair

or hose them down. Sheep dips or disinfectants give no

protection against radioactivity. When milking, you

should use rubber gloves and wear overclothes, such as an

overall or mackintosh. The gloves should be washed after

use and the overclothes left outside the farmhouse. You

would have to be very careful to prevent dust, hairs, etc.,

from falling into the pail if you were hand milking.

What is radiation sickness?

Radiation sickness is not infectious but it would reduce the resistance of the animal to other infection. If your livestock had received a heavy dose of radiation, whether entering their bodies from outside or because they had eaten feed contaminated with fall-out, they might sicken and die within a few weeks. Their flesh would be edible if they were killed before they became very sick. Even if they did not die as a result of the radiation, they would not make thrifty animals again and better use could be made of the feedingstuffs they would consume if they were allowed to live.

In areas where the level of radioactivity made it likely that a high proportion of the cattle would suffer from radiation sickness, arrangements would be made for the slaughter of the cattle and suitable disposal of the bones and offal as soon as practicable and possibly before any signs of radiation sickness had become apparent. You would be told if such arrangements were being made in your area and be given full instructions.

It would in fact be better not to slaughter until you had had some official advice, as it would be easier to preserve meat on the hoof than on the hook in the early days of a war of this nature and to keep animals alive would help the Government to organise a fair meat distribution.

How would you know if livestock had

radiation sickness ?

Radiation sickness is caused by radiation received

externally or by radiation received internally through

swallowing fall-out. Animals which had had a dose of

radiation severe enough to cause radiation sickness would

show irritability, diarrhoea, loss of appetite and apathy.

These symptoms might appear within a few days of the fall-out

coming down or might be delayed a week or two, according

to how heavy the fall-out was in your district or how

much had been ingested.

Would poultry, pigs and sheep be

affected by fall-out to the same extent as cattle?

Approximately, yes. Again, although they might get

radiation sickness, their flesh would be fit to eat. This

is because the radioactive material which is retained in

an animal's body goes into bones, and to its internal

organs rather than to the flesh. If you killed any

livestock for your family's use, you should not use the

bones or offal for food.

Is there any treatment for radiation

sickness?

For animals, no. But for humans, rest, good food and

good nursing are the best treatment.

How long would it be before it would

be safe to use milk and eggs from cows and poultry that

had eaten feed contaminated with fall-out?

It is impossible to say, unless it is known how much

fall-out they had swallowed. The safe answer would be to

suspect all milk for human consumption until you had had

expert advice.

If you could not send eggs to a packing station it would be best to put them into waterglass and store them until they had been tested. The risk of dangerous contamination in an egg, is, however, very small. They could be used if urgently needed for food.

Has fall-out any effects on breeding?

For a few weeks after exposure to massive doses of

radiation, the male animal is still fertile. If it is

used during this period there is a chance that its

offspring might be abnormal in some way. But if the

animal appears to be vigorous and healthy it is unlikely

to have received a massive dose. After this period of

fertility, the male animal may become partially or wholly

sterile, perhaps for as long as a year or so, after which

it is likely to recover its fertility.

With heavily contaminated female stock, some may become permanently sterile, others will remain fertile but with a chance that in some future generation, probably beyond our life-time, abnormal offspring may result. For breeding, then, the best course would be:

use the A.I. service if it is operating in your district;

do not use your male livestock for mating until several months after the attack, if they have obviously been affected;

if possible, use stock for breeding which has been under cover and away from fall-out.

You would be unlikely to see many ill-effects if you were to breed from contaminated stock. It would be better to use your bull than not to get your cow in calf, as the country would need all the milk your farm could produce.

Would fall-out affect hatching eggs?

It would be better to use eggs from birds that had

been exposed to fall-out than to stop breeding, but you

should try to breed from eggs from birds that had not

been exposed to radiation or had not picked up fall-out

whilst on open range.

In most areas the radiation from fall-out would not materially affect the growth of crops or damage seeds or young plants, but the crops might not be fit for human or animal consumption when harvested. Produce (except eggs, if needed) should not be marketed until tested for radioactivity.

If it were safe to be outside, it would be safe to prepare the ground for your crops, to sow seed or to plant out or to harvest crops, provided you took the precautions about washing. Also, if your crop was not planted when the fall-out came, it would be advisable to plough in the top soil so as to bury the fall-out as deeply as possible before planting. If you had a dusty job to do, and there are many on the farm, you should remember to wear a dust mask and to wash thoroughly afterwards.

Grain, potatoes or other roots stored in weatherproof buildings would be safe to eat. Roots in clamps would be safe to eat if after removal from the clamp all the soil were washed from them. Grain in stack would also be safe to use if several layers of sheaves from the roof were discarded and the outsides of the stack pared.

Fall-out in

the growing season

In the growing season the fall-out might be taken

into the plant either by the roots, if there were fall-out

in the soil, or by absorption through leaves on to which

fall-out had fallen. This would not make the plant

dangerous to handle, but it might possibly be enough to

make it dangerous to eat, especially in the case of leafy

plants where the leaf is the part normally eaten.

Fall-out just before harvest time

Fall-out at this time might make some crops dangerous

to eat, particularly where the parts exposed to the fall-out

are normally eaten. Fall-out might stick on to the heads

of corn or to the leaves of green vegetables. Rain would

be unlikely to wash it all off. If the fall-out came just

before harvest you should not market any vegetables or

cereals until you had had advice. It would be better to

delay harvesting if you were unable to store the crop.

Harvesting

If you were in an area so severely affected by fall-out

that at first you had to stay indoors most of the day, it

would be safer to wait a week or ten days after the

attack before harvesting the crop. Elsewhere, crops could

be harvested as soon as they were ready. But in all cases,

if there had been fall-out on your crop, it should be

kept on your farm until you had had advice.

It would be best to harvest a contaminated cereal crop with a combine, since this would be a less dusty job than handling sheaves. Whatever method you used you should take the precautions for your own safety described in the section Reducing the Risk from Fall-out.

Sometimes a crop might be saved for food, even if it seemed to be badly contaminated. Thus contaminated cereal crops might at least be partly decontaminated in the threshing process, which would remove the chaff, the part on which the fall-out had fallen. If there was a grave shortage of food in your district and your cereals had to be harvested to give an immediate emergency supply of flour, even though it was known they might be slightly contaminated, threshing would help to make the crop safer.

Potatoes

Potatoes (that is, the tubers themselves) and other

roots would not be likely to contain fall-out. If it were

safe to go on your ground it would be safe to harvest

your root and potato crop, but the roots should be

thoroughly washed before use.

Are there any genetic effects on

seed exposed to fall-out?

For practical purposes you need not worry about this.

Just sow your seed as usual.

Would it be safe to plant by hand in

contaminated soil?

If it were safe to be out, yes. But wash well

afterwards.

Would the use of sprayers help to

remove the fall-out from the top soil?

Not to any appreciable extent (experiments are being

carried out to find out whether deep ploughing or some

other method offers often the best means of removing fall-out

from the top soil). But it would be worth spraying the

yards near the house with water to keep the dust down and

wash it away.

Should crops growing in contaminated

land be limed and fertilised?

Yes, just as usual. The better your crop does, the

less would be the amount of the dangerous radioactive

chemicals in each unit of weight of the crop.

Your warden would tell you how long you and your men could safely stay outdoors. Do not exceed this time - use it for essential outdoor work. During the periods each day when you had to stay indoors, it would be almost as safe to work in your outbuildings provided they are at least as big and well constructed as a house. Buildings with asbestos, wood or corrugated iron sides would not give much protection against radiation from fall-out, and any time spent in them would have to be counted as part of your outdoor time. The higher the building the better; a high roof keeps the fall-out further away from you.

See that your men know about wearing dust masks, gloves, changing their clothes and washing after being out of doors. These simple precautions would reduce the risk appreciably. After dusty work or handling livestock it would also help if your men could change at the farm and travel home in clean clothes or at least change as soon as they reached home.

Arrange your work so that your men have as little travelling to do as possible. The time they take to get from their homes to your farm counts against the time they could spend in the open. The single men might be willing to live in the farmhouse for a week or two to reduce their travelling time and so be able to spend longer on essential jobs. A shift system to reduce travelling time might be feasible.

Is it necessary to change the

cropping rotation because of fall-out?

The roots of some crops do collect fall-out from the

soil more than others. But the best- thing to do would be

to carry on as usual unless the Agricultural Departments

advised you otherwise, either through their local

officers or on the radio. Cropping policy in war time

would be influenced by other factors than the effect of

fall-out on particular crops

Arrangements the Government is

making to advise you about your farming

The Agricultural Departments are training some of

their staffs to help you to deal with all the problems

discussed in this handbook, and to advise you about your

farming. These trained staff, like the warden and

everyone else, would have to take shelter from fall-out.

But afterwards, they would tell you whether your land and

produce were badly affected by fall-out and what to do

about them. And when the first few days and weeks were

over, and the main danger from fall-out had gone, they

would help you to tackle the other problems that might

then beset your farming.

Published by Her Majestey's Stationary

Office

PREPARED BY THE MINISTRRY OF AGRICULTURE, FISHERIES AND

FOOD

AND THE CENTRAL OFFICE OF INFORMATION

Printed in Great Britain under the

authority of Her Majesty's Stationary Office

by the Curwen Press Ltd., Plaistow, E.13.

Wt. 3692

S.O. Code No. 24-271*

PRICE ONE SHILLING NET

First published 1958: Reprinted 1959

|

This document is believed to be in

the public domain and was transferred to the Internet by

George Coney.

Last updated June 1999

Send mail to atomic@cybertrn.demon.co.uk